Dieser Artikel ist auch auf Deutsch verfügbar. Click here to find out more about the Ukraine!

My travel destinations are often unusual and sometimes even quite extreme. Previous destinations have included an abandoned nuclear bunker in Moldova, the Fukushima Evacuation Zone, a former Soviet Pioneer Camp in Belarus or an abandoned hotel in the Alps.

In mid-2018, we went to the Ukraine for two weeks to add a new entry to the list: the Exclusion Zone around the former Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. In contrast to most other destinations not a real insider tip anymore, day trips from Kiev are available for little money. Everything about the history of the nuclear accident has already been written, the usual pictures are well known from television or websites on the Internet. So if I was going to expose myself to the remaining radiation, I wanted to do something special again if possible. The tour was supposed to take at least two days, and as in Fukushima, I wanted to be able to speak with one of the few survivors again.

Clearly even this long article can only provide a rough overview of what it looks like within the Exclusion Zone. We shot around 1,200 useable photos with our three DSLRs, after all… 😉

Access permit and booking

Unlike in Fukushima, the dimensions of the Exclusion Zone established around the damaged Reactor 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986 remain unchanged to this day. The first boundary surrounds the reactor at a distance of 30 kilometers (30 Kilometer Zone), the second within a 10 kilometer radius (10 Kilometer Zone), and the third goes directly around the power plant. Since about 60% of the fallout released during the disaster went down behind the Belarusian border, Belarus has its own Exclusion Zone, the Polesie State Radioecological Reserve.

Access to the restricted areas is controlled by the military, patrols capture illegal intruders. Entering the Belarusian Exclusion Zone is only possible with a special permit. The Ukrainian Exclusion Zone may be entered either on application to the government or together with one of about 50 guides who work for about ten different tourist companies. The 10 Kilometer Zone can only be entered after sunrise and must be left before sunset. So you get a lot more time during the summer. But winter is actually the better time for photographers, because everything seems even bleaker and the missing leaves on the trees obstruct the views much less.

By far the largest and best-known companies are CHORNOBYL TOUR (chernobyl-tour.com) and SoloEast (tourkiev.com). Both offer daily departures on all weekdays from Kiev including transport and lunch, at the price of 70 to 80 Euros. These day tours are not worthwhile in my opinion, as the checkpoints of the 30-kilometer zone are only occupied starting from 10 AM and the tours arrive back in Kiev between 5 PM and 6 PM. If you factor in the travel times and lunch, only a measly few hours are left for the actual visit.

So we ended up booking a two-day tour with an overnight stay at a hotel in Chernobyl with SoloEast for 299 US-$ (around 270 Euros). These fixed tours are offered only about once a month and provide a much better value, since unnecessary travels and security checks are avoided and one gets significantly more time on site. In addition, the group size is limited to a maximum of 12 people and the guides will adapt the route to the wishes of the participants. Longer or more individual tours can be booked starting from 450 US-$ (400 Euros). After booking, a copy of the passport must be e-mailed to the organizer so they can register all participants with the authorities in advance.

If you want to see the buildings from the inside, you pretty much have to book at least a two-day tour. Otherwise there simply won’t be enough time, and entering is officially prohibited since an accident in 2011. The guides do not take the risk of getting caught on the less lucrative day trips.

Getting to Chernobyl

The journey by minibus to the checkpoint near the village Dytiatky (Дитятки) took about one and a half hours. Dytiatky already belongs to the District of Chernobyl, but is located just outside of the Exclusion Zone.

The day-trippers, in particular, were more interested in the thrill than in the actual consequences of a nuclear catastrophe. The tours were marketed with the slogan “Your friends will be jealous!” on the Internet, the waiting time at the checkpoint could be passed at the souvenir shop or by taking a selfie with “Gas Mask Man”. Some visitors had brought white full body “suits” made of thin plastic and were getting them on. Needless to say, the suits were not necessary, and they would not have been very effective anyways…

The Hotel

Since it was already past 11 AM, we checked in at the Hotel Desjatka (Десятка) and had lunch there. The property is located in the heart of the city of Chernobyl, 11 kilometers from the nuclear power plant, outside of the 10 Kilometer Zone.

Chernobyl is not a ghost town. There are at least two other hotels, several restaurants and supermarkets, cafes and a post office. However, the number of inhabitants has dropped to less than 700 from an original 14,000. All food and building materials have to be imported from outside, the drinking water comes from a pipeline.

There were also some strange souvenirs on sale at the hotel, including “Chernobyl Soap” with banana flavor (?) and T-shirts with a fluorescent print that glows green in the dark.

Driving School and Truck Repair Shop

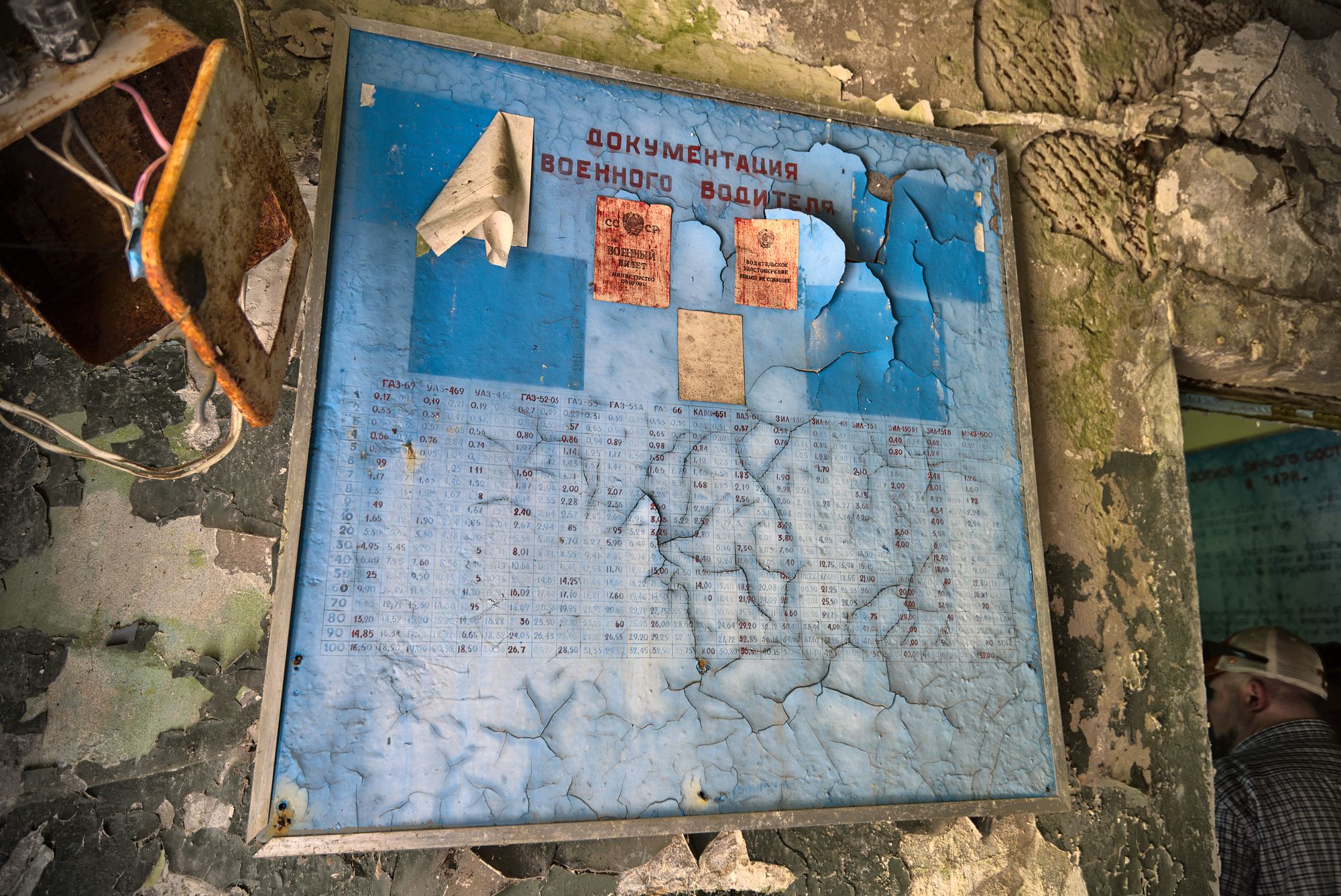

After lunch, we drove to a garage and driving school, which is located in close proximity to the Over The Horizon Radar DUGA-1. Here, military vehicles were repaired and the necessary drivers trained.

The interior of the driving school was probably already outdated back in the 1980s. The technology of Soviet trucks probably too, though…

On this board, the rides were still documented by hand and with a ballpoint pen. Computers, screens, printers? Nope! 😉

Over The Horizon Radar DUGA-1

Probably the best-known pictures from the Exclusion Zone are of the former Over The Horizon Radar DUGA-1 (дуга, english Bow). It was built to warn the Soviet Union of approaching intercontinental ballistic missiles. In the West, the facility was also known as the Russian Woodpecker because the radar signal produced a characteristic, “tapping” interference noise on many other radio frequencies. In some documents (unfortunately also in the strongly error-prone German Wikipedia article) the location is described as having been the receiver of the DUGA-3 radar. This is most likely wrong. DUGA-3 probably never existed, and a simple transmitter wouldn’t have required so much equipment.

The up to 150 meters high and 400 meters wide scaffolds support hundreds of individual antennas, which are connected to the receiving system via a myriad of wires and cables. The transmitter was located about 50 kilometers further east. Contrary to many claims, the plant was probably not primarily built near the nuclear power plant because of its high power consumption. The transmission power was only about ten megawatts – about two per mille of the power plant’s electric output, and not more than the total consumption of the city of Pripyat.

Rather, the location was probably simply chosen for security reasons. The area around the nuclear power plant was already protected anyway, so the top-secret radar complex with its huge antennas, large buildings and several thousand employees did not stand out that much. The inhabitants of the cities of Pripyat and Chernobyl could see the antennas from afar and probably knew what was going on there. But the West could only speculate until after the fall of the Iron Curtain and the opening of the Exclusion Zone. Ironically, DUGA-1 would no longer exist today if it weren’t for the nuclear disaster. Towards the end of the 1980s the system had already been superseded by observation satellites and was outdated. It was to be dismantled soon.

The signals from the antennas were transmitted to the receiving systems in the neighboring buildings via thick cables in wide shafts. If you look at DUGA-1 on a map, you might wonder why the antennas are aligned to the Northwest and not to the West (towards Europe) or to the East (towards the United States).

In fact, the shortest route between North America and Soviet territory is via the North Pole. So DUGA-1 mainly looks north and also covers a good chunk of Central Europe on one side. The American early warning system called Distant Early Warning Line (DEW Line) was set up in Alaska, Canada and Greendland for the same reasons and also looked towards the North Pole.

The processing of the radar signals was still carried out with huge analog computers at the time.

The remnants of the facilities covered two floors. The Over The Horizon Radar was able to detect rocket launches up to 8,000 kilometres away.

A complete hall was allocated just for the cooling systems of the – compared to today’s standards – very inefficient technology. But inefficiency was pretty much the standard case with the Soviets. If you look around the Technical Museums of the Eastern Bloc, you will mainly find large, heavy, hand-made blocks. There was a virtually unlimited supply of cheap labor and electrical energy.

The office and working areas were in a miserable condition after 30 years of decline, but on the other hand, they also had their very own charm.

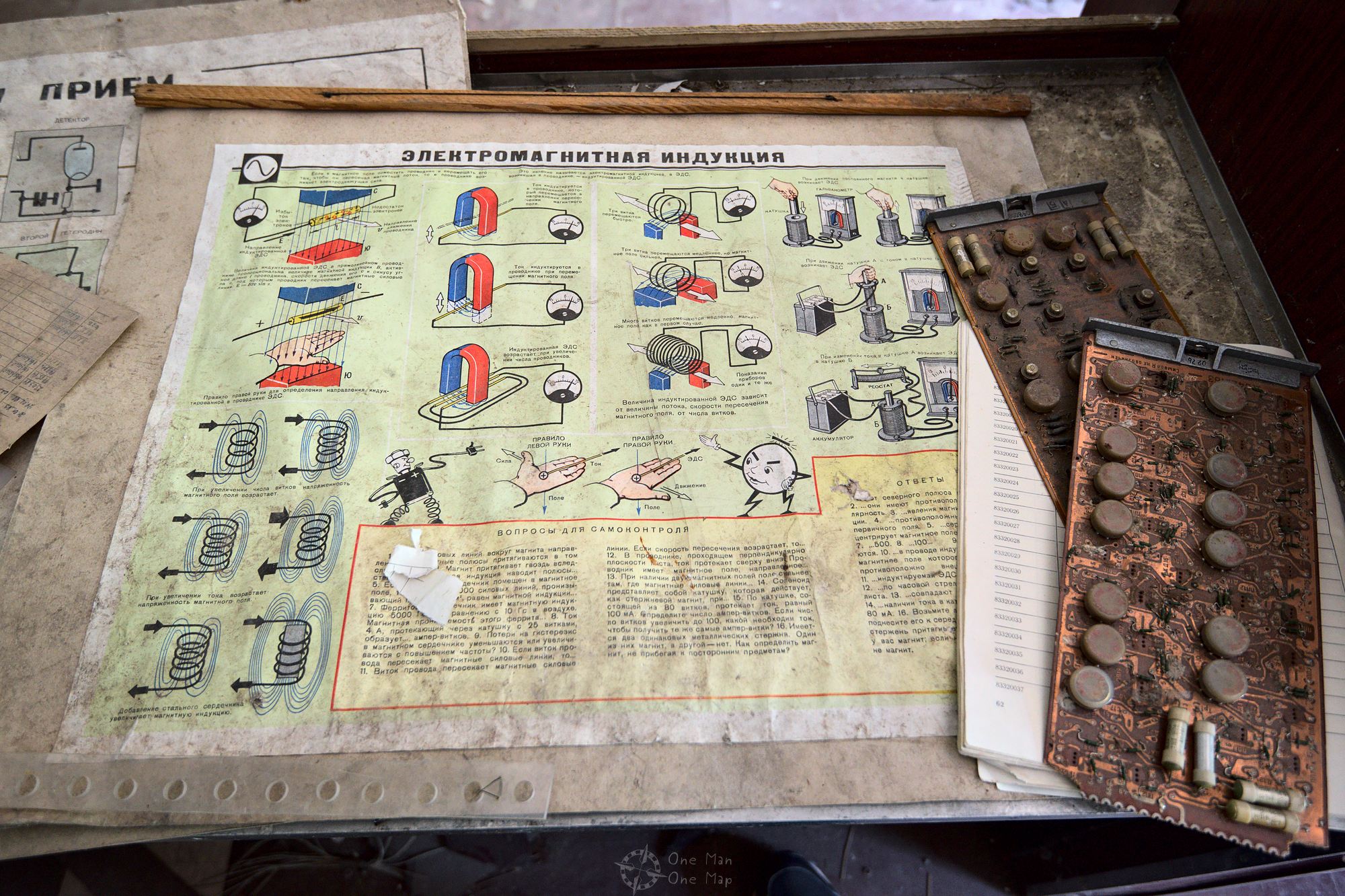

The complex also included a training centre for future staff. The prospective technicians and radar operators were educated on basic topics of electrical engineering and how to operate the huge radar system.

Artifacts from the time before the disaster could still be found everywhere, for example this newspaper article from June 8, 1985 about a friendly meeting between Mikhail Gorbachev and Todor Zhivkov, the then head of state of Bulgaria.

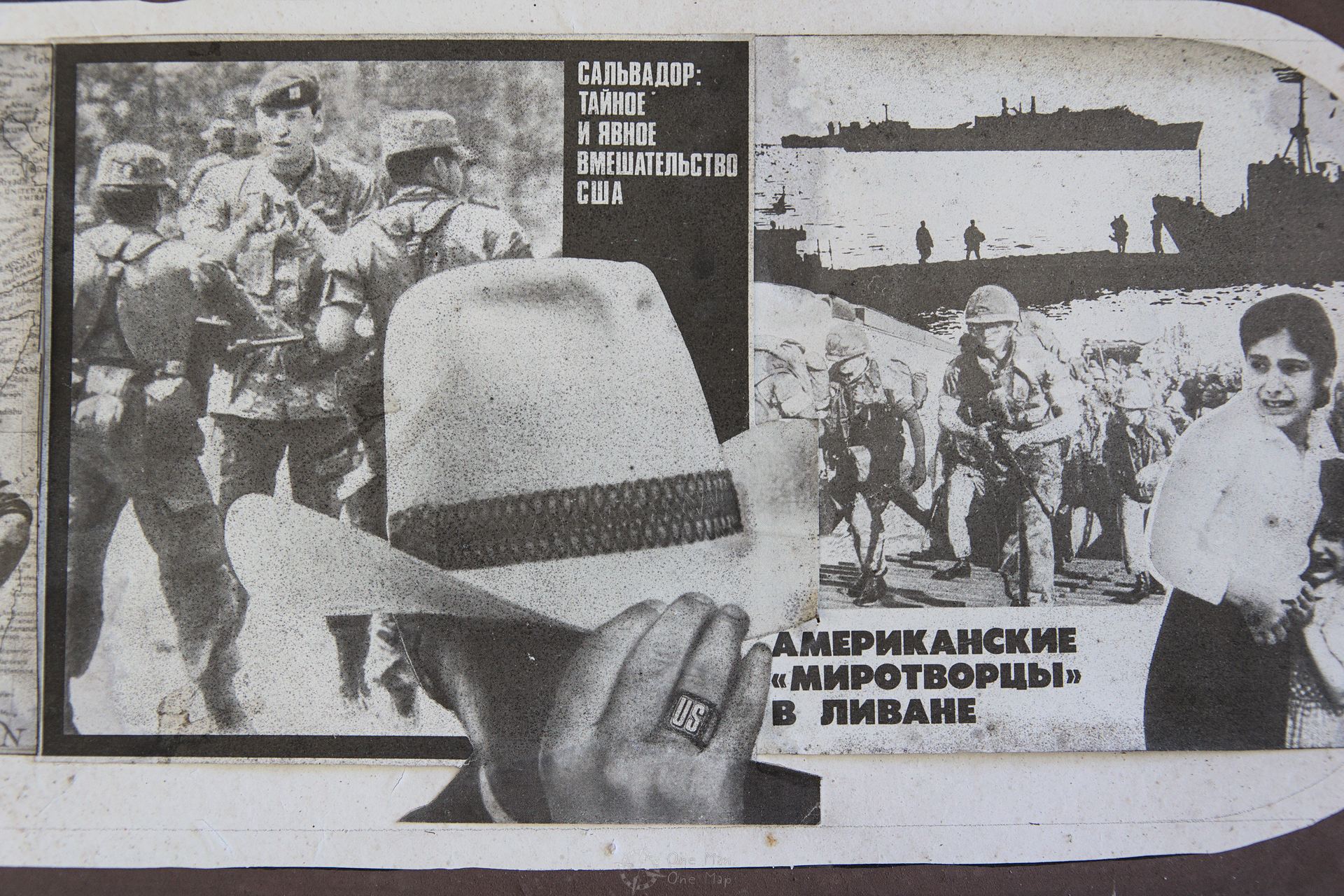

There was also no lack of propaganda against the enemy. Here, for example, the US interventions in El Salvador (left) and Lebanon (right) were exploited to create a mood against the enemy. The ongoing Soviet intervention in Afghanistan since 1979 fell under the table, of course.

On the way to the next stop we met some wild horses. According to our guide, an increased number of dead animals and plants with malformations was found in the time shortly after the accident, but nature has adapted very quickly. The restricted area has become a paradise for endangered species. In addition to the wild horses, wolves and bears can also be found here.

Birds are still much more affected by the radiation than other living beings. I can confirm that, we didn’t see or hear many birds during our stay. However, there are now also bird species that have adapted and are stronger than before. Yes, we have mutated nuclear super birds now, so to speak. What could go wrong 😉

The nuclear power plant

Time to turn to the cause of the whole catastrophe: the nuclear power plant. From the river Prypjat one has a nice view of the whole area with the total of six reactor blocks, of which only four were completed. Reactor block 4 exploded in 1986 after a meltdown, causing the disaster. The neighboring blocks 1, 2 and 3 were kept running and only shut down between October 1993 and December 2000. So the operating crews had to keep working in the contaminated power plant for up to 14 more years 😯

In front of the former reactor block 4 there is a statue which serves as a reminder of the disaster. Between 600,000 and 800,000 workers, so-called “liquidators”, had to work in close proximity of the the open reactor to shield it from the outside and build the first concrete sarcophagus. Inside the sarcophagus the situation of 1986 remains preserved. The fuel rods and other parts of the reactor merged into a mass called Corium, which has hardened somewhere under the reactor and continues to release radiation. Only radiotrophic fungi like Cryptococcus neoformans, which feed on the hard gamma radiation, can live there. The picture already shows the second sarcophagus, which is being put into position since 2016.

When the sarcophagus was finally erected, the government started working on the decontamination of the whole area. But the liquidators often aggravated the situation out of inexperience and e.g. contaminated the groundwater. Finally the region was given up completely and a total number of about 240,000 people within a radius of 30 kilometers was evactuated.

In addition to the current 30 Kilometer Exclusion Zone, large areas in Belarus, Russia, Europe and Asia were contaminated. Austria was one of the most contaminated areas, but the federal states of Bavaria, Saxony and Baden-Württemberg in Germany are also heavily contaminated. The radiation concentrates in mushrooms and wild berries, and therefore in the end in all wildlife. In some regions, therefore, about half of the hunted game still can not be released for human consumption to this day because the radiation limits are exceeded.

Construction of blocks 5 and 6 was started in 1981 about one kilometer from blocks 1 to 4. Despite the accident, authorities still tried to finish construction until 1988, when all works finally had to be stopped due to the high radiation. The incomplete cooling towers are now easily accessible and offer some beautiful, albeit spooky, perspectives for us photographers.

Inside this cooling tower I fully grasped for the first time what it means to be exposed to such levels of radiation. We walked in absolute silence through the gigantic concrete desert. It was a sunny, pleasantly warm day, the sky a perfect blue. Suddenly my personal Geiger counter started beeping. We had set the devices to a limit of 2 μSv/h, a value which had only been rarely reached in the previous hours. Now, however, the Geiger counter kept starting to beep at random, out of nowhere, showing values of up to 7 μSv/h. Either I had come too close to contaminated moss, or the wind carried radioactive particles picked up in the woods past us.

Human senses cannot detect radiation. You don’t see anything, don’t hear anything, don’t feel anything and don’t smell or taste anything. The Geiger counter can measure the radiation, but it doesn’t indicate a direction or any other useful information. Where to run to? What to avoid? It could be possible that the particles are already sticking to your body, or you already inhaled them. Maybe there is still salvation. maybe it is already too late. In moments like these you feel absolutely helpless and disoriented.

This six-meter-high graffiti was created by Australian artist Guido van Helton in 2016 for the 30th anniversary of the disaster. Although he had the permission of the authorities and was accompanied by the military, he could hardly wait to leave the restricted area again.

Pripyat

The ghost town of Pripyat (Прип’ять), named after the river of the same name, is located just three kilometers from the nuclear power plant. Before the disaster Pripyat was considered an absolute model city, mainly because it had only been founded in 1970 for the employees of the nuclear power plant. The nearly 50,000 residents enjoyed a higher standard of living than in the rest of the Soviet Union, they earned more and the average age was low. The evacuation of the entire city didn’t start earlier than 36 hours after the disaster. More than 1,000 buses were required to complete it.

Many people found a new home in Slavutych (Славутич), a new city built on the other side of the Dnieper specifically for the displaced workers, and some of them commuted to their workplace in the power plant by rail until the year 2000. Pripyat, on the other hand, suddenly became a ghost town. In the past there were no tall trees here, the entire city area had been cleared. Today, nature has recaptured almost everything. In many places the about 20 meters high trees are growing so dense that entire blocks of flats disappear in the thicket.

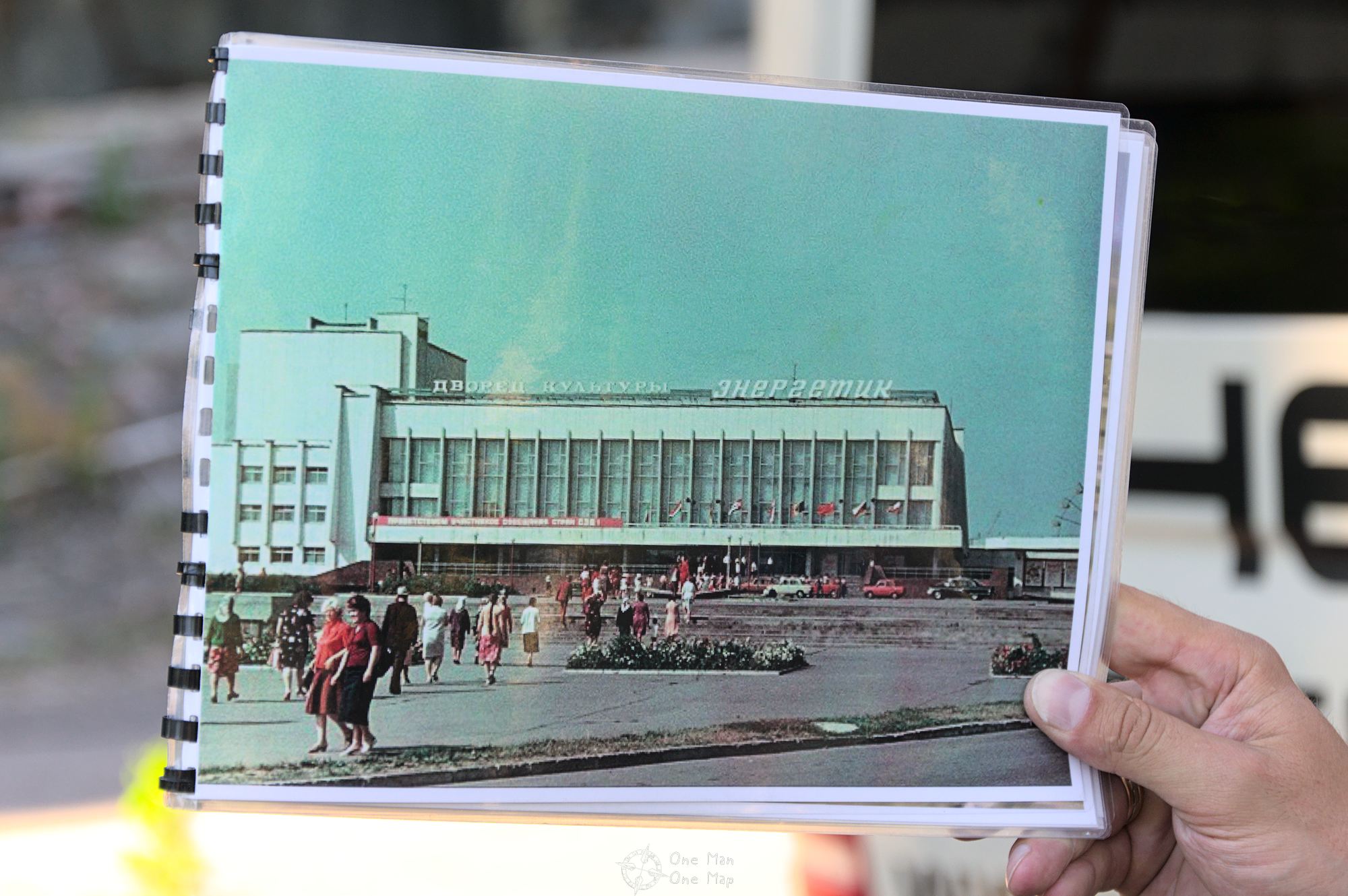

The hub of public life was, as always, the Palace of Culture. In Pripyat it had of course been proudly named Energetik (дворец культуры “енергетик”). Not only theater performances and celebrations took place here, but also sports competitions.

The Palace of Culture was equipped with its own sports hall and a swimming pool for the sports events.

From the sports hall we could already see the next and probably most famous place in Pripyat: the former amusement park.

The Amusement Park

There were amusement parks in every major Soviet city. But in Pripyat the reactor catastrophe on April 26, 1986 ensured that the planned opening of the park on May 1, 1986 never took place. Since then the amusement rides are rusting away, but even 30 years later all the gondolas are still attached to the ferris wheel.

A Ferris wheel and a carrousel were almost always present in the Soviet Union, but a car scooter as in Pripyat was a rather rare thing. All the more sad for the children that this amusement park never went into operation.

Hospital 126

Of course, a city with 50,000 inhabitants also needs good medical care. The Pripyat hospital also treated the first victims of the nuclear accident before they were transported to a special hospital near Moscow.

I don’t know about you, but I always feel a lot more scared in abandoned hospitals than in other lost places. Who knows what ghosts or radioactive bacteria still haunt in these realms…

The hospital was still used to treat the liquidators after the catastrophe, but at some point it must have been evacuated in a hurry. There was obviously no time left even for the removal of potentially still useful things, like ampoules with calcium solution.

During the chaotic evacuation of the city, many contaminated objects which the liquidators had brought from the power plant were left behind. Among them, for example, this metal badge, which still measured an incredible 488.7 μSv/h even after 30 years. For comparison: at most other locations in the Exclusion Zone our Geiger counters displayed less than 1 μSv/h, and during my visit to the Fukushima Evacuation Zone we had measured only 4 μSv/h even directly in front of the power plant 😯

The existence of a room in the basement in which the contaminated uniforms of the liquidators had been piled up was recently confirmed. Even after three decades the radiaton measured inside of this room still measured 1 Sv/h, enough to cause light radiation sickness within a short time!

Swimming pool “Lazurny”

The public swimming pool Lazurny (Плавательный бассейн “Лазурный”, english Swimming Pool “Azure”) with its characteristic diving platforms is also often seen on pictures from the Exclusion Zone.

The swimming pool remained open for a few years after the catastrophe, illegally, to provide the liquidators with some much-needed relaxation. According to an urban legend, an unfortunate combination of superstition and negligence is said to have led to the closure: Many of the liquidators apparently believed that vodka had a decontaminating effect. When one of the drunk workers fell from the diving tower to the edge of the pool and split his skull open, the administration was forced to shut down the illegal operation.

Middle School Number 3

Among the almost 50,000 inhabitants of Prypjat there were about 15,000 children and adolescents, in addition to many more from the surrounding villages. There were a total of 15 kindergartens and elementary schools, as well as five secondary schools, of which the middle school number 3 next to the swimming pool is probably best known. Almost everything was left behind here, from the furniture and teaching materials to the children’s handicrafts on the walls.

The scariest part are the many gas masks in children size which were left behind. Marauders ripped the masks out of the cupboards in search of a small piece of silver metal inside them, then simply left them lying on the floor.

The Kindergarten

Slowly the first day came to an end and we made our way back to the hotel. On the way we quickly passed through a former kindergarten in a small village.

Among the documents we also found lots of books and magazines, for example this magazine on pre-school education from the year 1975.

Abandoned children’s dolls in empty houses are always a creepy affair by definition, but these here were also radioactively contaminated and extra creepy…

When we left the 10 Kilometer Zone we passed through one of the security gates for the first time. You step into a cell which is surrounded by Geiger counters on all sides. If the measured values are below the limits, the small barrier is released automatically with a soft “clack”. The security post checks the minibus with a handheld Geiger counter in the meantime.

If the barrier hadn’t opened for one of the participants or if the minibus had been contaminated too heavily, we would have had a problem. Our guide had already warned us at the very beginning: Simple contaminations on the shoes, for example by radioactively contaminated ground or moss, could usually be removed with a little water and a disposable plastic brush. Contaminated clothing, on the other hand, was a completely different issue. A Chinese tourist allegedly sat on the contaminated ground just days before our visit and then had to go back to Kiev without her pants 😉

The Nuclear Ghosts Of Tchernobyl

We ate dinner at the hotel, I copied all our pictures onto my laptop, put the batteries in the chargers and we went to sleep. We wanted to go back to the 10 Kilometer Zone early in the morning, after all. Who could have guessed that we would have to deal with the nuclear ghosts of Tchernobyl that night …

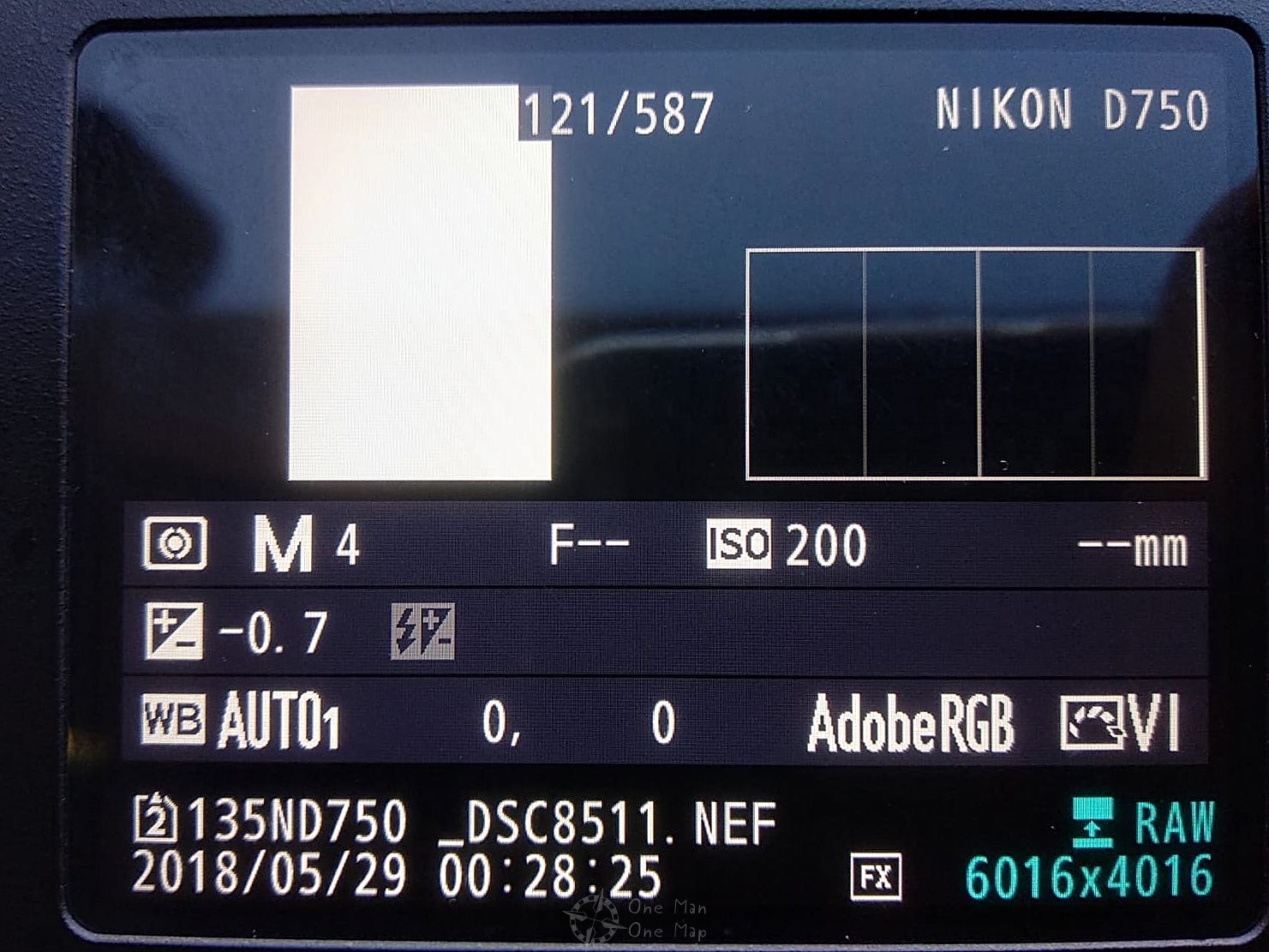

At four o’clock in the morning I was suddenly awakened by a loud, aggressive beeping sound. The culprit was quickly found: my Nikon D750 not only beeped for unknown reasons (the camera has never beeped even once in the last two years), but the autofocus light flashed at the same interval. The battery had just been charged a few hours earlier but was suddenly empty. The on-off switch was already set to “off”, so I sleepily pulled the battery out of its compartment, finally ending the beeping and blinking, put the battery in the charger and closed my eyes again. Luckily I didn’t have a closer look at the rest of the room, so I only noticed the new image on the memory card the next morning:

Supposedly, the camera had taken a completely white image at 00:28:25 AM, in portrait format, even though the camera had been placed horizontally on a cabinet. The metadata contained seemingly meaningless values: four seconds exposure time, unknown aperture setting (!), unknown lens focal length (!). Although the camera worked normally over the whole of the second day, we were kind of glad we did not book a three-day tour 😯

Only after our return weeks later I had the courage to look for ghost images within those white pixels. Up until now I couldn’t find any…

Visiting Valentina Ivanova

On the second day we set off to the former village Teremtsi (Теремці) at the eastern end of the Exclusion Zone to visit Valentina Ivanova. Our guide had called her the day before, and she was delighted to have us on her property. The nearly 30-kilometer drive from Chernobyl was not very pleasant. Teremtsi on the Dnieper had formerly consisted of about 500 houses, with its own school and a larger port facility. In the meantime the road had turned into a somewhat better dirt road, the houses had disappeared between the dense vegetation, and more than once our guide was not sure if he had taken the right turn.

But in the end we arrived safely at the property. Valentina Ivanova belongs to the very small group of current inhabitants of the Exclusion Zone who still live there illegally. She came to Teremtsi as a young woman, married in 1968 at the age of 22, and worked at Hospital 126 in Pripyat as a nurse. After the accident, she was responsible for the initial care of the injured firefighters and the liquidators. Her husband was drafted as a liquidator.

Even though the surroundings of their house are still so heavily contaminated today that many parts of it are forbidden from entering, the two withstood all attempts of eviction. Her husband died in 2008. Mrs. Ivanova wants to be buried alongside him and strictly rejects a move to a retirement home outside the Exclusion Zone. We met the now 72-year-old in a very good mood.

The illegal inhabitants and the authorities have settled into a routine of co-existance within the Exclusion Zone. Access to electricity and food is provided, and in the event of problems (such as impassable roads in winter), residents can call the security posts by phone. They help each other or ask the guides to bring some items. Early in the morning before leaving Chernobyl we had stopped at a supermarket and worked through Mrs. Ivanovas grocery list.

Relatives are also allowed to enter the Exclusion Zone on up to 14 days a month, which Mrs. Ivanova’s son-in-law currently took advantage off to catch fish in the river Dnieper. She herself took care of the garden as she did every day. In addition to a small vegetable garden for self-sufficiency, the many flowers were her pride.

After our visit to Mrs. Ivanova we climb on one of the shipwrecks stranded in the Dnjepr. Surely a worthwhile thing for non-ferrous metal thieves, but hardly anyone gets that far into the exclusion zone.

Summer Camp “Emerald”

The former Summer Camp Emerald (база отдыха изумрудный, Baza Otdykha Izumrudnyy) was located near the cooling basin of the nuclear power plant. Besides the 100 wooden houses there was also a cinema, a library, a dance hall, a boat dock and a supermarket for the little guests. As far as I know it was not easy to get one of the highly contested spots in this camp. The children’s parents at least had to work in the nuclear power plant or hold a higher rank within the party. The architecture of the broken huts and houses reminded me a lot of my visit to the Pioneer Camp “Druzhnyj” near Minsk in Belarus.

After the disaster the camp was evacuated immediately, and the liquidators settled down here. Among their legacy one can also find some gas masks.

The Summer Camp “Emerald” apparently also exists within the computer game S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl. No wonder, it’s a quite creepy place, and the drawings on the huts are not helping. Similarities to well-known characters from movies of the class enemy are pure coincidence, by the way 😉

Construction materials already seemed to have been scarce in the 1970s. We came across more than one ceiling which had obviously been tacked together from the remainders of wooden shipping crates and pallets.

Goodbye, Chernobyl

Before we went back to Kiev, we stopped once more in the city of Chernobyl. Part of the group went to the supermarket to buy some ice cream, but I walked around a bit and took some more pictures of typical Soviet art.

Goodbye, Chernobyl, maybe I’ll visit you again some day. In the meantime the next blog posts will continue to take us through the Ukraine. And it isn’t necessarily going to get less scary… 🙂

More pictures of Lost Places can be found in the corresponding category.

This post was written by Simon for One Man, One Map. The original can be found here. All rights reserved.