Dieser Artikel ist auch auf Deutsch verfügbar. Click here to find out more about Albania!

For an overview on Albania, have a look at the introductory post.

Albanias bunkers are constant companions on the way through the country. No matter where you go, cities, mountains, roads or beaches – the bunkers are always there. On average there are about 5.7 per square kilometer. They were all built under ex-dictator Enver Hoxha, under gigantic efforts, without any sense or reason: during his entire reign there was not a single armed conflict.

Most of the bunkers are very small, just big enough for a single armed person. There are over 100,000 of this variety. It would therefore be pointless to try to make a map, and even today there is no complete list of all bunkers in Albania. I will limit the scope of this article on general background information and detailed information on the large nuclear bunkers in Tirana (Museums Bunk’Art 1 and Bunk’Art 2), a prominent bunker on the Llogara Pass, the Gjadër Air Force Base and a submarine Bunker near Porto Palermo. A map with the positions of these five bunkers and a GPX file for download can be found at the very end of the article.

The history of the bunkers

As the leader of the communist party “Democratic Front of Albania” Hoxha had taken power after the Second World War. Unlike his allies, however, he always adhered to the ideology of Stalin and Mao and stood up to any softening or even murderization. He had already quarreled early with Yugoslavia under Tito. The war with Greece had never ended on paper. In 1968, Albania rose from the Warsaw Pact, and US President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 led to the break with the Chinese.

Towards the end, traded only with neutral countries like Austria or Sweden. In 1976, the foreign relations broke off completely. Private property was severely curtailed, foreign credit banned and every opposition brutally crushed. It followed a decade of almost complete isolation.

Already in 1968, after the invasion of the Warsaw Pact in Czechoslovakia, Hoxha had finally been confirmed in his constant paranoia. It could only be a matter of time before someone attacked resource-rich Albania. Whether it was the Yugoslavs, the Greeks, the Italians, the Warsaw Pact, NATO, or anyone else, that did not matter in principle. Albania was definitely in danger and had to defend itself without regard for losses.

The entire population was to engage in combat in an emergency – a concept developed by Mao, which had already proven during the Partisan fight in the Second World War. Albania had finally freed itself from its occupiers as the only country in Europe on its own.

Following the model of partisans in World War II, the Albanian forces should again provide the enemy with a devastating guerilla war. The partisans had withdrawn at that time in the easily defensible mountains and driven from there repeatedly attacks on the difficult to defend flatland. Hoxha did not want to let it get that far. By building hundreds of thousands of bunkers, he wanted to make sure that the enemy could already be stopped on the flat land.

Between 1968 and 1986, the construction of a total of 750,000 bunkers was planned. According to recent surveys, however, “only” about 170,000 were actually built. The battered Albania simply could not do more. Small bunkers were made entirely in factories and then brought to the destination, larger ones had to be made in the traditional way. The bunker program and the costs for special steel from abroad weighed heavily on the construction industry and the state budget. Important resources were deducted from major problems, such as the lack of housing and the broken roads.

The most commonly encountered bunker type is the mushroom-shaped Qender Zjarri (alb. The dome has a diameter of up to three meters, inside an armed person can stand upright. In order to save concrete, cavities were filled with earth on site. The round dome simply makes enemy projectiles bounce off, a realization taken from the Soviet Union.

At longer distances there are Pikë Zjarri called command bunkers. These are spherical, but with up to eight meters in diameter significantly larger. One of these bunkers weighed up to 400 tons. The prefabricated concrete parts produced in factories were assembled on site into a kind of igloo.

The construction of the bunkers took precedence over everything else. If a position was good for the defense, for instance because there was a small hill there and you could see far, then a bunker was built there. Even if it was a field, a schoolyard, a park or even a cemetery. Tirana was particularly heavily fortified. From the city center, bunkers run through the entire area in 50 concentric circles.

In addition to the battle bunkers, an unknown number of air and nuclear bunkers were built under company buildings, administrative buildings, schools, residential buildings, etc. These could not be manufactured in factories and put together on site, but had to be individually planned and built in a traditional way. Again, Hoxha did not trust anybody. The construction teams were changed at regular intervals so that nobody knew too much about a facility. The planners were often eliminated later. For example, Josif Zagali, architect of Qender Zjarri and colonel of the Armed Forces, was imprisoned for eight years.

Hoxha not only ordered the construction of the bunkers, but of course trimmed the propaganda machine to the alleged danger from the outside. As in other communist and socialist-ruled countries, indoctrination began very early. Already in kindergarten, three-year-olds were warned to be on their guard and to report suspects.

From the age of twelve children were trained to go to the next bunker in case of emergency and to defend it. All families had to keep the bunkers clean and ready for action in the vicinity of their homes and apartments. At least twice a month, combat exercises took place, each lasting up to three days.

At peak times, more than a quarter of the population (about 800,000 out of three million people) was somehow part of the armed forces. In addition, large parts of the government, state-owned enterprises and public institutions were involved in the planning. In the case of conflict, therefore, almost every Albanian would actually have been a cog in the war machine.

Despite these preparations, the Albanian defense system was extremely inefficient and would not have stood up to attack. The training was bad, there was not enough fuel and ammunition, weapons and uniforms were outdated and of poor quality. The supply of tens of thousands of one-man bunkers with supplies remained an unsolved problem. Defense Minister Beqir Balluku openly denounced these circumstances in 1974 and demanded instead of the many bunkers a classic, strong army. Hoxha immediately responded to the criticism by summarily executing Balluku and his supporters.

After the death of Hoxha and the collapse of the Communist system, some of the bunkers were reused as warehouses, houses, cafes, restaurants, etc. Only a few were actually part of fighting during the civil war-like lottery uprising in 1997.

Bunk’Art 1

The (most likely?) largest bunker runs through a complete mountain near Linza in Tirana. In 2014, the nuclear bunker built for the highest levels of the political leadership was converted into a museum and art center called Bunk’Art. It is best to combine the visit with a ride on Mount Dajti, as the valley station of the Dajti Express cable car is right next to the entrance to Bunk’Art 1. We used bus line 1 from the Clock Tower (Kulla e Sahatit) stop. It is a short walk from the Market Hippo station to the ticket office.

Admission costs 500 Lek (about 4 Euro), for the audio tour there is an additional charge. One should plan several hours for the visit, since arrival and departure take a while and there is really a lot to discover.

In the case of an attack, dictator Hoxha, the prime minister and the president would have found refuge here with their closest confidants and selected members of the secret police Sigurimi. Of course they wouldn’t have had too bad a time. The dictator would have had access to a study room, a reception room with a secretary, a living room and a befitting bedroom.

Quite a a luxury compared to nuclear bunkers of other leaders, for example the Bunker 42 in Moscow. It is easy to see in what kind of parallel world the dictator and his followers lived. While there weren’t enough homes and apartments for the normal population outside, people were starving and the infrastructure was crumbling, Hoxha would have slept in silk bed linen in his nuclear bunker. Most Albanians were not aware of the existence of this bunker until the museum was opened.

On five floors, 106 rooms with a total area of over 3000 square meters were dug into the mountain. However the floors are located one behind the other in the mountain and not above and below each other. Therefore at the end of a floor you go down one level via a staircase to the beginning of the next floor.

Long side tunnels branch off from the main tunnels again and again. The tunnel network supposedly is about two kilometers long.

Many of the rooms have been converted into exhibition spaces. Each one is dedicated to a specific theme in the history of Albania, such as the occupation by Italy, the partisan struggle during the Second World War, the communist regime, the persecution of the opposition, the bunker program or the overthrow of the communist regime.

Many artifacts, such as military communications technology, were inaccessible prior to the opening of this museum. Even smaller absurdities such as the bunker school (I wonder if the children would have still needed a high school diploma in the event of a nuclear war?) are addressed.

A large meeting room with a stage is also not missing. Since its rededication to a museum in 2014, it is available for events.

One of the showrooms is dedicated to the use of poison gas as a weapon of war. Here you can not only find the usual gas masks, but you can flood the room with stage fog at the touch of a button, which emanates hissing from a nozzle on the floor. A macabre kind of fun …

Not all parts of the bunker are accessible, and you don’t get to see a lot of infrastructure such as air filters, diesel generators, etc. But maybe that’s just because the bunker was not finished. Construction began in 1978, and after Hoxha’s death in 1985, his successors quickly lacked the money and motivation to finish it. Even the planned entrances and exits were not finished. Today you enter the museum via inconspicuous side entrances.

Bunk’Art 2 (Objekti Shtylla)

Of course there are many more big bunkers for the political leadership. One of them is located next to Skanderberg Square, almost directly under the Town Hall. It was part of the last wave of the bunker program. Construction began in 1981 and it was completed in 1986, so after the death of the dictator. Following the example of Bunk’Art 1, the bunker was converted into an underground museum and called Bunk’Art 2.

The entrance fee is 500 Lek (about 4 Euro). One should plan about one to two hours for the visit.

A series of portraits under the concrete dome at the entrance commemorate some of the victims of the many purges done by former secret police Sigurimi. The concrete dome itself was damaged by activists during the construction of the museum, who saw a glorification of the former regime in it. The museum management then decided not to remedy the damage and to make it part of the installation.

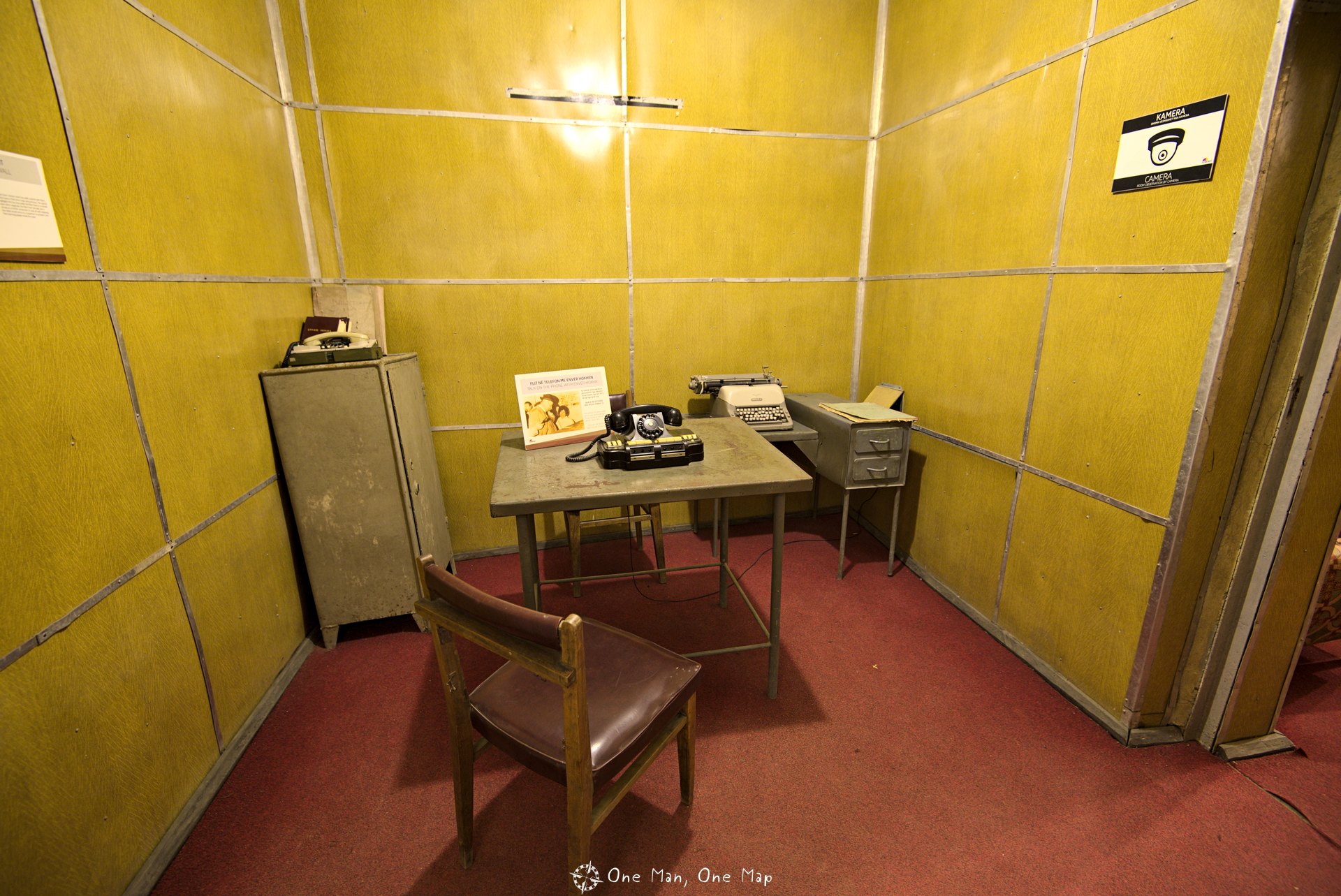

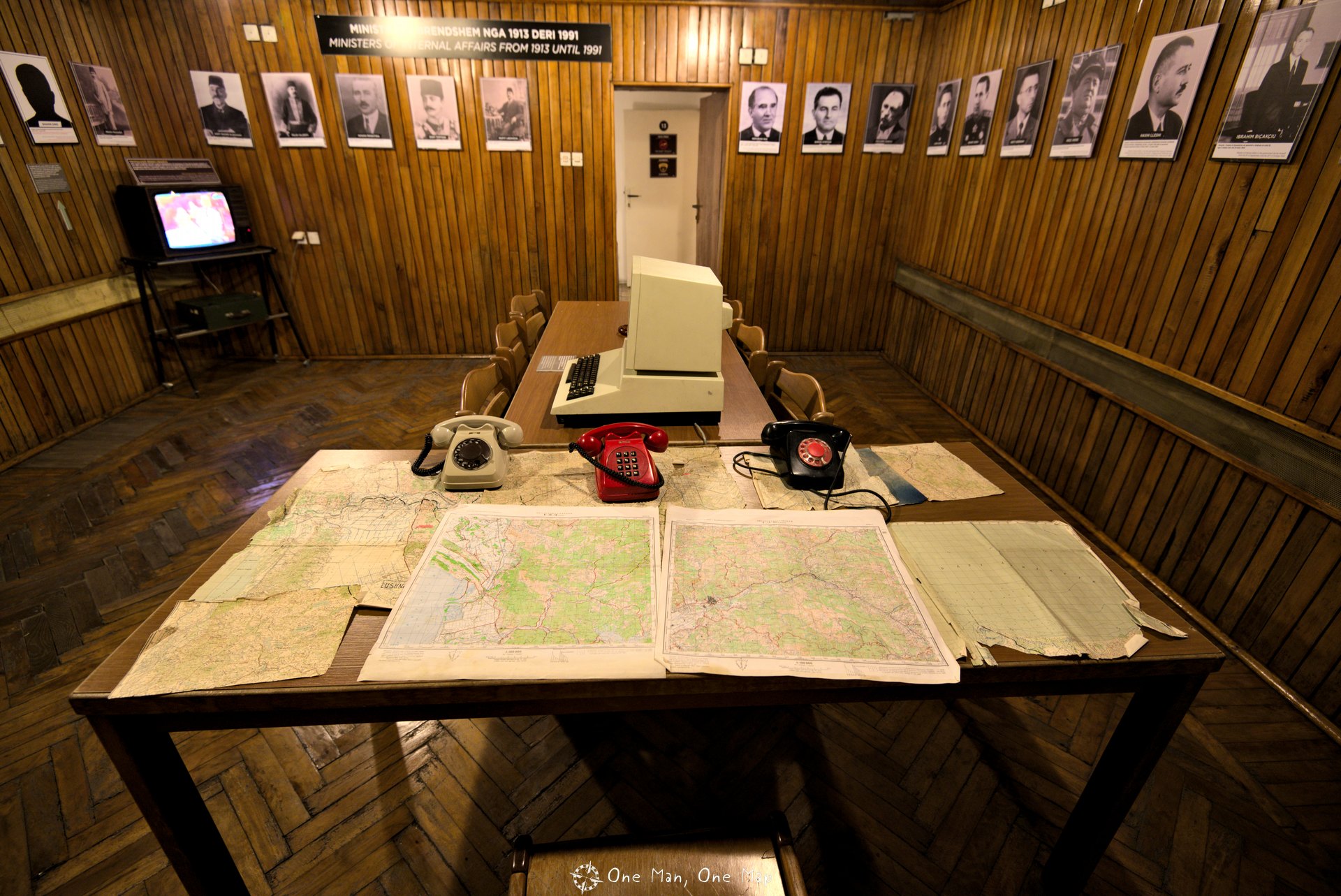

Most of the very professional designed underground spaces deal with the history of secret police Sigurimi, from its beginnings in the partisan regiments to their actions against actual or supposed enemies of the regime.

Even in this nuclear bunker, the members of the party would have found themselves in a familiar environment. There were comfortable study rooms, bedrooms and conference rooms in the typical style of the 1970s. Sometimes even with – compared to the state of the art of Albania back then – quite modern computers 😉

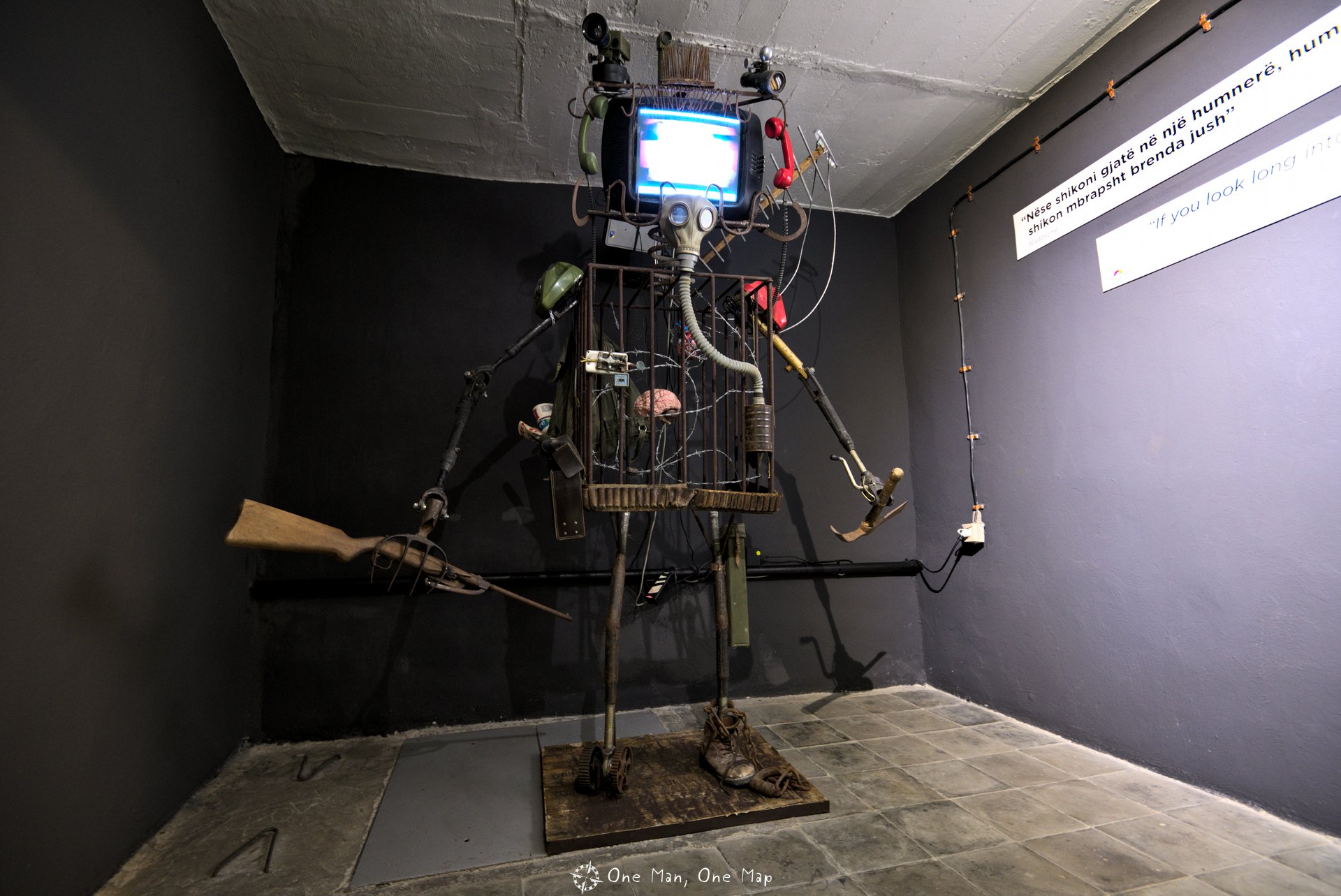

As the name “Bunk’Art” implies, both museums also see themselves as art galleries. I am usually not a big fan of Modern Art, but the atmosphere in the bunker and some of the sculptures were quite interesting.

The bunker on the Llogara Pass

You can also randomly stumble across some of the big bunkers. We just wanted to make a brief stop at this building ruin on the Llogara Pass, move our legs a little and enjoy the view. But then a concrete tube suddenly blocked our view of the sea, and we already knew what we would find down there. The hill is located about 650 meters above sea level, on good days you may even see Italy or the island of Corfu at the horizon. An ideal place for a large command bunker.

In addition to the main entrance on the front there is a side entrance. What the big tube should have been good for was not clear. Maybe the actual weapons were to be installed later.

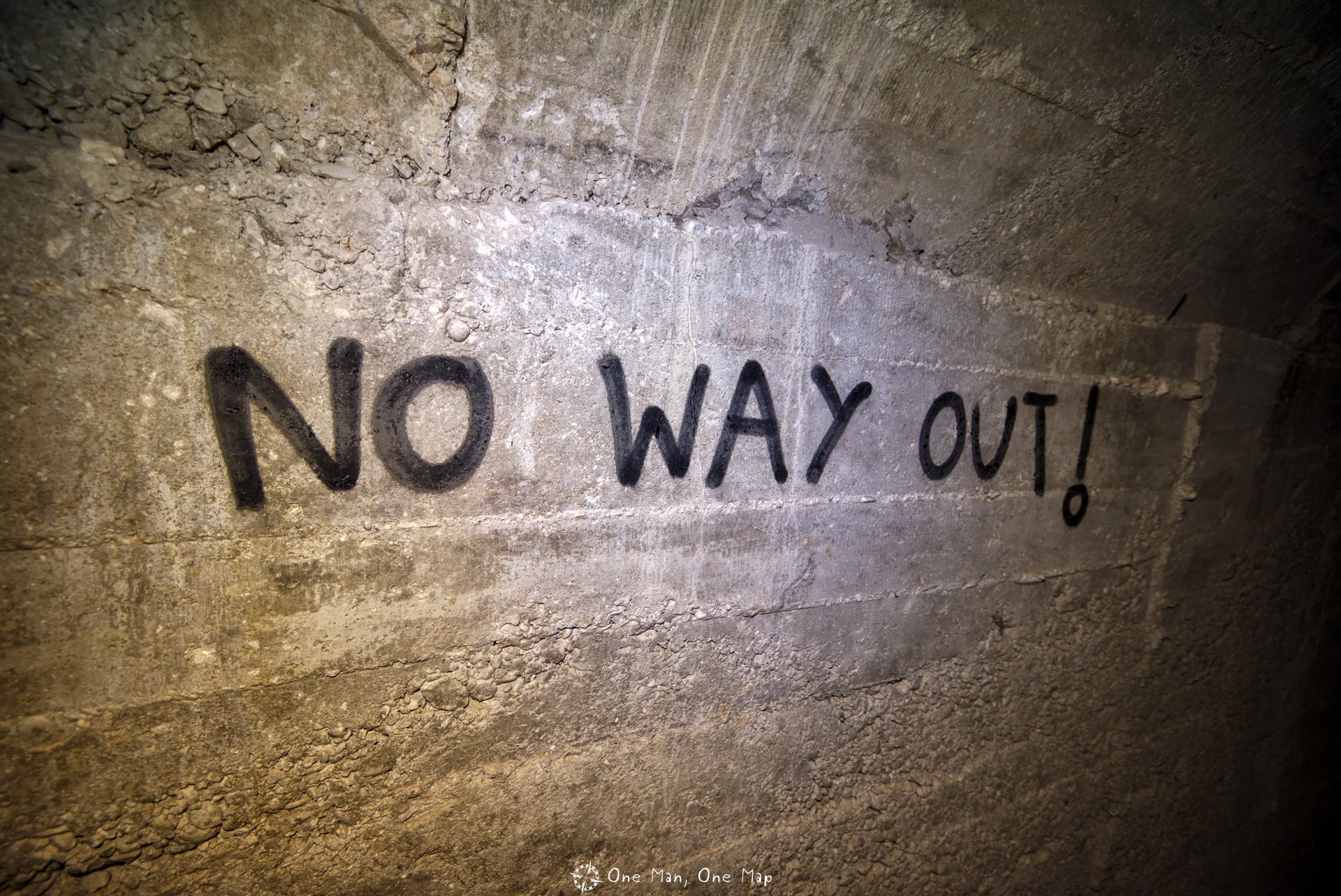

The main corridor extends many meters deep into the mountain, various rooms branch off to the side. In the middle the main corridor bends at a 90-degree angle and leads to the second entrance.

At least we were not alone down here. A friendly mouse had turned the bunker into its home…

Behind the large concrete tube at the front there are two larger halls. Probably ammunition and / or smaller weapons would have been stored here. Heavier weapons would not have fitted through the small passageway.

Air Force Base Gjadër

There were not just bunkers for people, but also for whole airplanes, ships and submarines. The Gjadër Air Force Base for example has several underground galleries. The fighter aircraft were brought to safety here.

Caution: Although the site looks like a complete ruin today, it is still an active and guarded military area! Access is prohibited!

Submarine Tunnel Porto Palermo

Porto Palermo was an important military base during the reign of Enver Hoxha. Between 1955 and 1968, the Soviet Union stationed twelve Whiskey Class Soviet submarines at Vlorë. After the withdrawal of Albania from the Warsaw Pact, Hoxha appropriated the four submarines which were controlled by Albanian soldiers and stationed them in Porto Palermo.

In order to be able to leave the sheltered bay in the event of a blockade, construction of a 650 meter long and 12 meter high submarine tunnel was started. The four submarines fitted inside completely, one after the other. From the sea, the outer tunnel entrance was not visible.

Although the military base itself has been abandoned for a long time and only consists of ruins, it is not possible to enter the facility. The Albanian Coast Guard uses the quayside as a base and also guards the rest of the terrain.

Map

Friends of Lost Places will love the next post. Things will get huge again when we visit the gigantic abandoned power plant in Fier… 😉

This post was written by Simon for One Man, One Map. The original can be found here. All rights reserved.